The US spends around a trillion dollars annually trying to prevent metallic corrosion, an electrochemical reaction that happens when metals oxidize and start to rust. Researchers have now calculated how much corrosion is steadily increasing global carbon emissions by tackling this unexpectedly pernicious problem.

Global steel production has been rising steadily for decades—and because steel has poor resistance to corrosion, part of that demand is to replace steel used in construction materials that have become corroded over time, in everything from bridges to automobiles. Reducing the amount of steel that needs to be replaced due to corrosion could have measurable effects on how much greenhouse gases are produced to make steel, said Gerald Frankel, co-author of the study and a professor in materials science and engineering at The Ohio State University,

Though previous studies have estimated the current economic cost of corrosion to be about 3 to 4% of a nation’s gross domestic product, this new study, led by Ohio State alum Mariano Iannuzzi, is the first to quantify the environmental impact associated with steel corrosion.

The study was recently published in npj Materials Degradation.

“Given society’s reliance on coal fuel, iron and steel production is one of the largest greenhouse gases emitters of any industry,” said Frankel. “But most of the costs associated with the industry actually stem from the energy that goes into creating steel, and that energy is lost as the steel reverts to rust, which is similar to its original form of iron ore.”

The time it takes steel to corrode largely depends on the severity of the environment and the alloy composition, but this environmentally expensive issue is only getting worse, said Frankel.

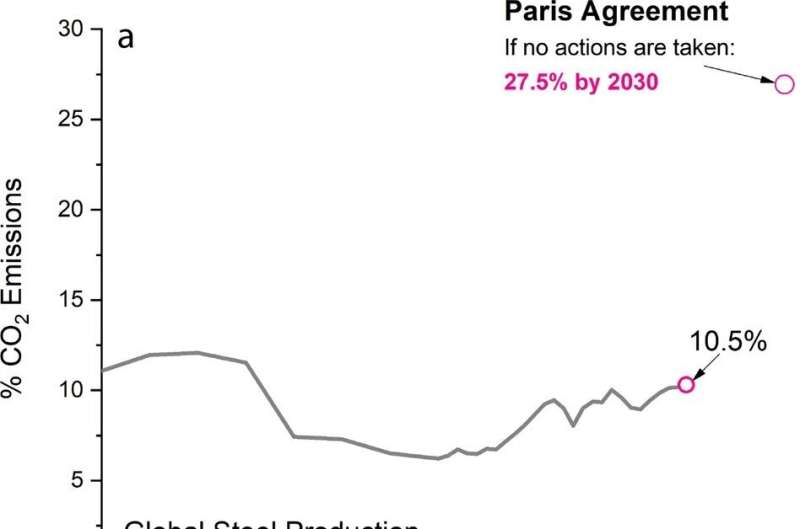

Using historical carbon dioxide intensity data to estimate carbon dioxide levels per year beginning from 1960, the researchers found that in 2021, steel production accounted for 27% of the carbon emissions of the global manufacturing sector, and about 10.5% of the total global carbon emissions worldwide. Corroded steel replacement accounted for about 1.6 to 3.4% of emissions.

Yet, as the report pointed out, there is some good news. Over the past 50 years, the energy consumption of the steelmaking process has decreased by 61% as a result of regulations imposed on the steel sector.

Notwithstanding this progress, Frankel stated that the study’s findings should prompt worldwide governments and business leaders to modify and coordinate their strategies for managing corrosion and steel production.

“Coordinated international initiatives, together with reducing global steel demand, might better improve global corrosion management techniques and substantially lower the surge in greenhouse gas emissions we’re seeing owing to continuously replacing damaged steel,” he said.

If actions to improve steel’s carbon footprint aren’t taken soon, the study notes that greenhouse gas emissions produced by the steel industry could reach about 27.5% of the world’s total carbon emissions by 2030, with corroded steel representing about 4 to 9% of that number. Such a result would make the goals set by the Paris Agreement to limit Earth’s warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius as well as the U.S.’s own domestic climate goals almost completely unfeasible.

The study notes that management strategies such as taking advantage of machine learning technologies could be one of the best chances we have to reduce Earth’s carbon dioxide levels.

That said, if humans cannot meet these conditions, the consequences for Earth’s climate will be dire, so more people need to be made aware that a low-carbon steel industry is needed to prevent such a dystopia, said Frankel.

According to Frankel, “Global warming is a societal concern that requires coordination of several multidisciplinary approaches.” In terms of the significance of contributing to the situation, “our effort is bringing to light an issue that seems to have gone under the radar.”