Hey there, history buffs and curious minds! Have you ever wondered what Nigeria was like before the British came along and drew lines on a map? We often hear about colonial rule, but what about the centuries of intricate societies, powerful kingdoms, and unique governance structures that thrived on this land long before? It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking pre-colonial Africa was a wild, untamed place without order. But let me tell you, that couldn’t be further from the truth!

Nigeria, as we know it today, is a relatively modern construct. Before the amalgamation of 1914, this vast geographical area was a vibrant mosaic of hundreds of distinct ethnic groups, each with its own rich culture, traditions, and – crucially – its own sophisticated political system. These weren’t haphazard arrangements; they were well-developed, functional societies with their own ways of maintaining order, administering justice, and ensuring the well-being of their people. So, buckle up, because we’re about to embark on a fascinating journey to explore the diverse political powers that truly existed in Nigeria’s pre-colonial era.

The Broad Spectrum of Governance: Centralized vs. Decentralized

When we talk about political systems in pre-colonial Nigeria, we can broadly categorize them into two main types: centralized and decentralized structures. Think of it like this: some societies had a single, powerful leader or a ruling elite at the top, much like a modern monarchy or empire. Others were more community-focused, with power distributed among various groups, making decisions through consensus, almost like a direct democracy. Both systems had their strengths, and both adapted to the specific needs and environments of the people they governed.

What Were the Major Types of Political Structures in Pre-Colonial Nigeria?

This question gets right to the heart of our discussion! As we’ve hinted, the major types really boil down to those highly structured, hierarchical systems and those more dispersed, communal ones. We’re going to dive into some prominent examples that beautifully illustrate this spectrum, from the vast empires of the north and west to the unique, “stateless” societies of the east.

Centralized Powers: Kingdoms and Empires of Authority

These were the large, often expansive, political entities characterized by a strong central authority, a hierarchical administrative system, and often a standing army. They controlled vast territories and populations, and their leaders wielded significant power.

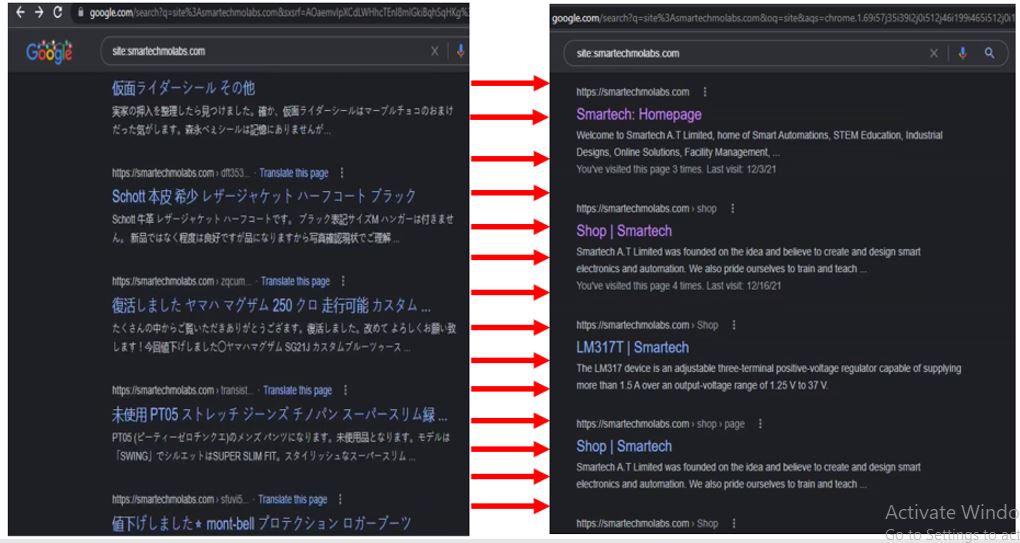

The Hausa-Fulani Emirates (Northern Nigeria)

Imagine a vast expanse of land in northern Nigeria, dotted with walled cities, bustling markets, and centers of Islamic learning. This was the domain of the Hausa-Fulani emirates, a powerful and highly centralized system that was shaped by the 19th-century Fulani Jihad.

Historical Context and the Rise of the Caliphate

Before the jihad, there were independent Hausa city-states, each with its own “Sarki” (ruler). These included famous names like Kano, Zaria, Katsina, and Gobir. While they were sophisticated, it was the Sokoto Caliphate, established after the successful jihad led by the revered Islamic scholar Usman Dan Fodio in 1804, that truly consolidated power. This brought most of the northern Hausa states under a unified, Islamic-based political and religious authority.

Political Structure and Key Figures

At the very top of this highly structured system was the Sultan of Sokoto, who served as the spiritual and political head of the entire Caliphate. Below him were the various Emirs, who ruled individual emirates (provinces) on his behalf. An Emir was not just a political leader; he was also the religious leader, ensuring adherence to Islamic law.

Think of it like a well-oiled machine. Each Emirate had a complex administrative structure. Key officials included the:

- Waziri: The Emir’s chief minister and most trusted advisor, overseeing general administration.

- Madawaki: The commander of the cavalry and military affairs.

- Galadima: In charge of the capital city and its surrounding areas.

- Ma’aji: The treasurer, managing the emirate’s finances.

- Sarkin Ruwa: Overseeing fishing and water resources.

- Sarkin Pawa: Head of the butchers.

Governance and Law: The Role of Sharia

The Hausa-Fulani system was a theocracy, meaning that religious law deeply intertwined with political governance. Islamic law, or Sharia, was the guiding principle for justice, administration, and social conduct. Cases were heard in Alkali courts, presided over by Alkalis (Islamic judges) who were highly knowledgeable in Sharia. The Emir’s court was the highest judicial authority, and his word, guided by Islamic tenets, was supreme. This system, while powerful, also emphasized accountability to divine principles, influencing even the traditional rulers’ decisions.

Economic Foundations

The prosperity of the Hausa-Fulani emirates was largely built on trans-Saharan trade. They controlled major trade routes, exchanging goods like kola nuts, gold, and slaves for salt, textiles, and horses from North Africa. Agriculture, particularly the cultivation of grains, also formed a crucial backbone of their economy.

The Yoruba Kingdoms (South-Western Nigeria)

Moving southwest, we encounter another formidable, centralized power: the Yoruba kingdoms. These were complex monarchies known for their rich cultural heritage, intricate political systems, and a fascinating balance of power.

Historical Context and the Influence of Ile-Ife

The Yoruba people trace their origins to Ile-Ife, a city revered as the spiritual cradle of the Yoruba civilization. From Ile-Ife, various powerful city-states and empires emerged, with the Old Oyo Empire being one of the most prominent. These kingdoms were typically self-governing but shared a common cultural identity, language, and belief system, including the worship of Orishas (deities).

Political Structure: The Oba and His Council

At the head of each Yoruba kingdom was the Oba (king). The Oba was not just a political leader but also a sacred, often divine, figure. His beaded crown (Ade) was a powerful symbol of his authority. However, unlike some absolute monarchies, the Oba’s power was not absolute. Instead, it was carefully balanced by powerful councils and societies.

In the Old Oyo Empire, the Alaafin (the Oba of Oyo) was checked by the Oyomesi, a council of seven powerful non-hereditary chiefs. The Basorun was the head of the Oyomesi and could even compel an Alaafin who acted tyrannically to commit suicide by presenting him with a calabash of parrot’s eggs. Talk about checks and balances!

Beyond the Oyomesi, influential secret societies like the Ogboni also played a significant role. The Ogboni, composed of respected elders and influential figures, served as a judicial body, religious authority, and a check on both the Oba and the Oyomesi. This intricate system ensured that power was distributed and that accountability mechanisms were in place, making it a remarkably resilient form of governance.

Governance and Justice

Yoruba governance involved a clear hierarchy from the Oba to various chiefs (Baale for towns, Oloja for market towns) and compound heads (Olori Ebi). Justice was administered through a system of courts, with the Oba’s court as the highest. Disputes were often resolved through mediation and reconciliation, aiming to maintain social harmony.

Economic Foundations

The Yoruba economy was primarily agrarian, with staple crops like yams, maize, and cassava. They were also skilled artisans, producing intricate carvings, textiles, and metalwork. Trade, both local and regional, was crucial, connecting different Yoruba kingdoms and extending to neighboring peoples.

The Benin Empire (South-South/Mid-Western Nigeria)

Slightly to the southeast of Yorubaland, we find the illustrious Benin Empire, a highly centralized and militarily powerful kingdom of the Edo people, renowned for its artistic prowess and sophisticated political organization.

Historical Context and the Divine Oba

The Benin Empire’s history is ancient and impressive, stretching back centuries. At its core was the Oba of Benin, a divine ruler whose authority was virtually absolute, seen as a direct link between the people and the spiritual world. The Obas of Benin created a vast empire that exerted significant influence over its neighbors.

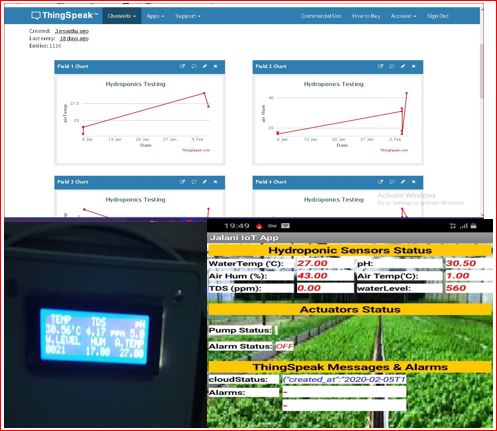

Political Structure: A Tight Ship

The Benin Empire was a marvel of centralized administration. The Oba was at the apex, but he governed through a highly structured bureaucracy of chiefs. These included:

- Uzama Nihinron (Kingmakers): A council of hereditary chiefs who were the traditional kingmakers.

- Egharevba (Palace Chiefs): A large body of non-hereditary chiefs who held administrative, military, and ceremonial roles within the palace and across the kingdom. They formed a powerful civil service, responsible for implementing the Oba’s directives.

This system ensured efficient administration and control over a large territory. The Oba’s authority was reinforced by a strong military, which maintained order and expanded the empire’s reach.

Governance and Economy

Governance in Benin was highly ritualized, with the Oba’s divine status underpinning his authority. Justice was dispensed through a formal court system. Economically, Benin thrived on trade, particularly in pepper, ivory, cloth, and later, the transatlantic slave trade. Its exquisite bronze and ivory artworks, like the famous Benin Bronzes, were not just artistic masterpieces but also served to legitimize and glorify the Oba’s power.

Decentralized Powers: Communities of Consensus and Shared Authority

In stark contrast to the grand empires, many pre-colonial Nigerian societies adopted decentralized political structures. These were smaller, more egalitarian communities where power was diffused than concentrated in the hands of a single ruler or elite.

The Igbo Communities (South-Eastern Nigeria)

When people talk about pre-colonial Nigeria Hausa Fulani Yoruba Igbo, the Igbo often stand out because their system was so different. Imagine a society without kings, queens, or even a standing army in the conventional sense. That’s largely what you’d find in Igboland!

Historical Context: “Stateless” Societies

The Igbo people, predominantly in southeastern Nigeria, were known for their segmentary or “stateless” societies. This doesn’t mean they were without governance; rather, it implies the absence of centralized monarchical rule. Their political organization was a testament to direct democracy and communal decision-making.

Political Structure: Power to the People (and Elders)

How did they govern themselves without a king? It was fascinatingly complex and highly democratic at the local level. The fundamental unit of governance was the extended family or Umunna. Decisions affecting the wider community were made through:

- Village Assemblies (Oha-na-eze): All adult males (and sometimes influential women) would gather to discuss and decide on matters affecting the community. Debates were often long, but decisions, once reached, were binding by consensus.

- Council of Elders (Ndichie or Ama-ala): Composed of respected lineage heads, Ozo title holders, and wise men, this council advised the community and often acted as a judicial body for disputes.

- Age Grades (Uke): Groups of individuals born within a certain period, who performed specific community functions. Younger age grades might be responsible for communal labor (clearing paths, building markets), while older ones provided security or enforced community laws.

- Title Societies (Ozo, Ofo): Achieving titles like Ozo (for men) or membership in powerful women’s associations like the Umuada (first daughters of a lineage) conferred immense respect and influence, giving members a significant voice in community affairs and dispute resolution.

Governance and Justice: Consensus is Key

The Igbo system emphasized individual freedom, communal participation, and consensus. Conflicts were typically resolved through mediation, arbitration by elders, or community adjudication. The Earth Goddess, Ala, also played a crucial role in maintaining moral order, with offenses against her leading to severe sanctions.

Economic Foundations

Agriculture, particularly the cultivation of yams, was the cornerstone of the Igbo economy. Trade, both local and long-distance (e.g., the Arochukwu Confederacy’s extensive trade network), was also vital.

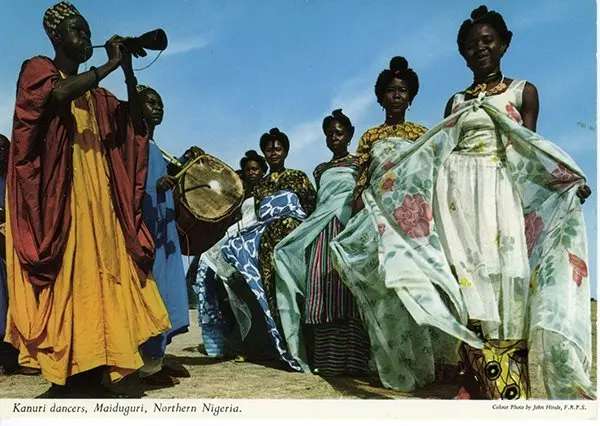

Other Decentralized Examples: Tiv and Niger Delta Communities

While the Igbo are a prime example, many other Nigerian groups also practiced decentralized forms of governance:

- The Tiv (Middle Belt): Known for their segmentary lineage system, where kinship ties formed the basis of their social and political organization. Leadership was often based on age, influence, and oratorical skills rather than hereditary titles. The Tiv’s culture, deeply rooted in their heritage, continues to thrive in Nigeria today, offering a window into the values and practices of this resilient community.

- Ijaw, Efik, and Ibibio (Niger Delta/Cross River): Many communities in the Niger Delta, particularly the Efik city-states like Calabar, evolved unique governance systems. While some, like Calabar, developed a form of centralized leadership around the Obong, others remained more decentralized, with powerful secret societies like the Ekpe/Egbo playing significant roles in administration, law enforcement, and trade regulation. These coastal communities thrived on their extensive trade networks, particularly in palm oil and, historically, the slave trade.

Commonalities and Contrasts: A Comparative Look

When we look at the pre-colonial Nigeria political systems centralized vs decentralized, we can spot some interesting patterns.

Similarities:

- Importance of Kinship: Family, lineage, and clan ties were fundamental to social and political organization across almost all Nigerian societies.

- Role of Tradition and Custom: Oral traditions, customary laws, and ancestral practices formed the bedrock of governance and justice.

- Spiritual Underpinnings: Religious beliefs and spiritual leaders often played significant roles in legitimizing authority, administering justice, and ensuring community well-being.

- Agrarian Base: Most pre-colonial Nigerian economies were primarily agricultural, supplemented by trade and crafts.

Differences:

- Degree of Centralization: This is the most obvious difference – from the absolute rule of an Emir to the highly communal decision-making of the Igbo.

- Leadership Succession: Hereditary succession was common in centralized monarchies, while in decentralized societies, leadership was often based on age, merit, or title acquisition.

- Judicial Systems: Formal courts and written (or religiously codified) laws were more prevalent in centralized states, while decentralized societies relied more on community arbitration and consensus.

- Social Structure (pre-colonial Nigeria social structure): Centralized states often had more rigid class structures, while decentralized societies tended to be more egalitarian, though still with hierarchies of age, wealth, and achievement.

What Was the Role of Religion in Pre-Colonial Nigerian Governance?

Religion was not just a private belief; it was deeply interwoven with the fabric of society and governance across virtually all pre-colonial Nigerian communities.

In centralized states like the Hausa-Fulani emirates, Islam provided the legal framework (Sharia) and moral compass for the entire political system. Emirs were both political and religious leaders. Among the Yoruba, the Oba’s divine status was crucial to his legitimacy, and religious cults like Ogboni played direct roles in political and judicial affairs. Orishas like Sango (god of thunder and justice) often had direct implications for how justice was perceived and administered.

In decentralized societies, indigenous religious beliefs were equally vital. For the Igbo, the Earth Goddess (Ala) was paramount, overseeing morality and fertility, and violations against her were serious community offenses. Priests and diviners held significant influence, guiding community decisions and mediating disputes based on spiritual insights. Religious festivals marked important communal events and reinforced social cohesion.

African Cultural Heritage: A Living Treasure of Identity, Pride, and Power

Pre-Colonial Nigeria Economy

Let’s quickly touch on the backbone of these societies. Beyond the political structures, understanding the pre-colonial Nigeria economy helps us appreciate their self-sufficiency and interactions.

Most pre-colonial Nigerian societies had primarily agricultural economies. Yams, cassava, millet, and sorghum were staple crops. Animal husbandry was also practiced, especially by the Fulani. Craft production was highly developed, including weaving, pottery, metalworking (iron, brass, gold), and leatherwork.

Trade was vital. Communities exchanged goods through local markets, while long-distance trade routes connected various regions and even extended across the Sahara and to the coast, facilitating interaction with European traders. Currencies varied, from cowries to iron rods and salt. This robust economic activity supported the various political systems we’ve explored.

Pre-Colonial Nigeria Traditional Rulers

The title of “traditional ruler” carries immense weight in Nigeria even today, a direct legacy of the pre-colonial era. These individuals – be they Emirs, Obas, Obis, or community elders – were not just ceremonial heads. They were active leaders with defined roles:

- Judicial: Administering justice, settling disputes.

- Executive: Enforcing laws, managing community resources.

- Legislative: Sometimes making laws, or overseeing assemblies that did.

- Spiritual: Performing rituals, acting as intermediaries between the people and the divine or ancestors.

Their authority, whether absolute or constrained by councils, was deeply respected and integral to the functioning of their societies.

Did Pre-Colonial Nigeria Have Written Laws?

This is an excellent question! The answer is nuanced. In the northern Hausa-Fulani emirates, with the advent of Islam, Sharia law was codified and written in Arabic texts. So, yes, in these regions, written laws existed and were administered through the Alkali courts.

However, for most other parts of pre-colonial Nigeria, particularly in the south, legal systems were based on unwritten customary laws. These were passed down through generations orally, understood through traditions, proverbs, and precedents. Justice was administered based on community norms and the wisdom of elders. While not “written” in the modern sense, these customary laws were robust, well-defined, and effectively managed societal order and conflict resolution.

What Were the Main Kingdoms in Pre-Colonial Nigeria?

Beyond the big three (Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba, Igbo), several other significant kingdoms and powerful polities dotted the landscape:

- Kanem-Bornu Empire: Located around Lake Chad, this was one of Africa’s oldest and longest-lasting empires, with a rich history of Islamic scholarship and trans-Saharan trade. Its power waxed and waned, but it remained a significant force in the northeast.

- Nupe Kingdom: Situated along the Niger River, the Nupe developed a strong centralized kingdom with a sophisticated administrative system.

- Jukun Kingdom (Kwararafa): A powerful entity in the Middle Belt, known for its military might and influence over various groups.

- Igala Kingdom: Located at the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers, it was a significant trading power that interacted with both northern and southern states.

These kingdoms, alongside the numerous smaller communities and decentralized societies, truly illustrate the incredible diversity of pre-colonial Nigeria.

The Enduring Legacy of Pre-Colonial Governance

The arrival of colonial powers fundamentally disrupted these established systems. The British, with their “indirect rule” strategy, often tried to adapt or even manipulate existing structures (especially in the North and West) or impose new ones (often in the East, where centralized authority was lacking). This led to significant challenges and resistance.

Yet, despite over a century of colonial and post-colonial transformations, the echoes of these pre-colonial powers resonate deeply in contemporary Nigeria. The traditional rulers, though their political powers are now largely ceremonial, still command immense respect and play crucial roles in their communities. The cultural values, legal precedents, and social structures forged in those earlier times continue to influence identity, communal relationships, and even modern political discourse.

Conclusion

So, there you have it! Pre-colonial Nigeria was far from a blank slate. It was a continent within a country, brimming with diverse, functional, and often highly sophisticated political systems. From the vast, centralized empires of the Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba, and Benin, with their intricate hierarchies and checks and balances, to the egalitarian, consensus-driven communities of the Igbo and Tiv, each society developed governance structures uniquely suited to its needs.

Understanding these foundational “powers” is not just an academic exercise; it’s essential for truly appreciating Nigeria’s historical depth, its cultural richness, and the resilience of its peoples. It reminds us that governance, in its many forms, has always been a cornerstone of human organization, long before external forces sought to redefine it.

Unique FAQs

How did leaders in decentralized societies like the Igbo gain authority without kings?

In decentralized societies like the Igbo, leadership was earned through merit, wisdom, age, and achievement, rather than hereditary succession. Individuals gained influence by excelling in farming, trade, or by acquiring prestigious titles like Ozo. Their authority stemmed from the community’s respect for their wisdom, integrity, and ability to mediate disputes and articulate community consensus, not from a centralized royal power

What role did women play in pre-colonial Nigerian political systems?

While often less visible in formal leadership roles, women held significant political and social power in many pre-colonial Nigerian societies. In Igboland, women’s associations like the Umuada (daughters of a lineage) and market women’s groups wielded considerable influence, ensuring moral conduct and even initiating collective action against injustice. In Yoruba kingdoms, powerful female figures like the Iyalode held significant political and economic sway, representing women’s interests in the Oba’s council. Their roles were often complementary to male-dominated structures, providing crucial checks and balances.

Were there conflicts between these diverse pre-colonial powers?

Absolutely. While trade and alliances were common, conflicts also occurred. These could stem from disputes over land, trade routes, tribute collection, or political dominance. For example, the Old Oyo Empire engaged in wars with neighboring kingdoms to expand its influence, and the Fulani Jihad led to significant transformations and conflicts in the North. These interactions, both peaceful and violent, shaped the shifting political map of pre-colonial Nigeria.

How did the geographic environment influence the type of political system adopted by different groups?

Geography played a crucial role. The vast, open savannas of the North facilitated the movement of large armies and the establishment of centralized empires like the Hausa-Fulani, supported by trans-Saharan trade. The dense forests and fertile lands of the Southwest allowed for the development of powerful Yoruba city-states. In the heavily forested and riverine areas of the Southeast, the terrain often made large-scale political centralization difficult, contributing to the rise of smaller, independent Igbo communities and the focus on riverine trade for the Delta peoples.

Did pre-colonial Nigerian societies have a sense of “nation” or shared identity?

While the concept of a single “Nigerian nation” didn’t exist before colonialism, many groups had strong ethnic identities and shared cultural values within their broader linguistic or regional communities. For instance, the Yoruba people, despite their various kingdoms, shared a common language, origin myths (from Ile-Ife), and cultural practices. Similarly, the Hausa and Fulani, despite their distinct origins, were unified by the Sokoto Caliphate and Islam.